Previous “Cars…” Tour Stop | Return to “Cars…” Tour Map | Next “Cars…” Tour Stop

Professor Herbert F. Moore, born in 1875, can be called the savior of American railroads. In the early 1900s, many railroads were having problems with their tracks shattering from fissures in the steel. Over twelve thousand rails failed per year costing a fortune in repairs, damaged goods, and human lives. For many years, nobody was able to determine the cause, and the greatest progress was the development of a detector car that was able to detect a potential rail failure with the use of gyroscopes.

Moore was an Assistant Professor of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics (1907-1914) and a Research Professor of Engineering Materials (1914-1944) at Illinois. In 1930, Moore, who began research of metal fatigue in 1919 and was considered an expert, was approached by the Rail Manufacturer’s Technical Committee and given a grant to attempt to find the cause of the rail failures.

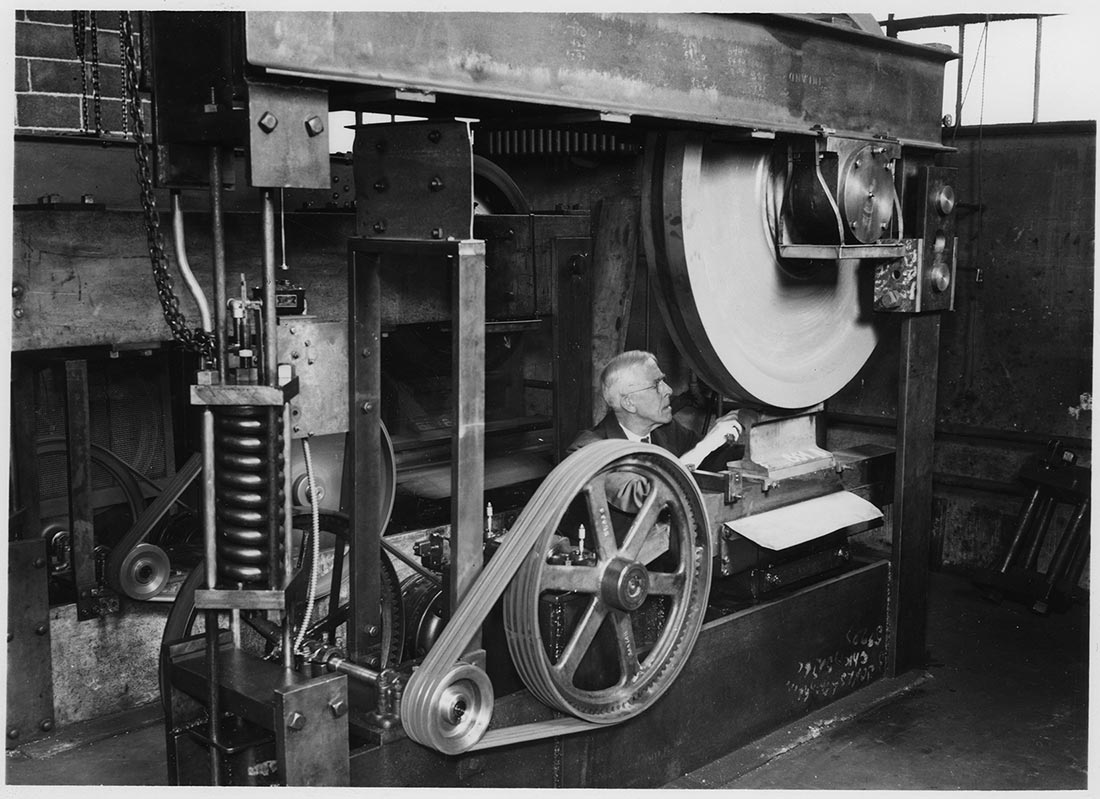

Herbert Moore Conducting Stress Tests on Rails

Moore’s first instinct was that the rails were failing due to stress from day-to-day use. Using many different techniques to stress rail samples, from a full sized locomotive running on a treadmill system to bending and impact testing, Moore was never able to find a definitive reason as to why the rails failed. To his team’s surprise, many rails that have tested positive for fissures had not failed in the destruction tests. His research led him to believe that the fissure problem was most likely not caused by stress, but rather by chemical and metallurgical problems.

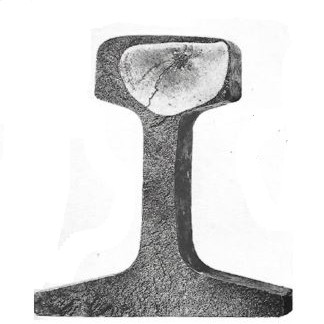

Image of Rail with Shatter Crack

The first clue came to Moore in a paper written by I. C. Mackie, a Nova Scotian steel mill metallurgist, hypothesizing that hydrogen was present in excess in the shattered rails. This realization launched a three year study into hydrogen and steel rails. Moore found that when steel was cooled too quickly after forging, the steel was able to absorb a massive amount of hydrogen. The hydrogen then collected around the impurities in the steel, leading to fissures that could shatter after repeated stress. Moore and his team were able to create a controlled cooling process that slowly cooled the steel so that it did not absorb too much hydrogen. In 1939 the new rails were ready to be used. Within just a few years, millions of controlled-cooled rails had been laid and still to this day, none have ever failed. Moore and his team had saved the railroads over 100 million dollars of damages and was hailed as the saviors of the railroad system.

– Aeronautical Lab A. Formerly the Locomotive Testing Lab, this is where Moore conducted tests on railroad tracks using locomotives. This building was demolished late summer of 2018 due to structural concerns. The marker on the map is where the building was located.

– Talbot Laboratory. In the west stairwell there is a painting of Moore. Directions: Enter the west doors (off of Wright Street) and go up the set of stairs. It is between the first and second floor. Accessible directions: Enter the east doors (on the Bardeen Quad) and take the elevator on the east side to the second floor. Then follow the hallway to the west staircase. The painting can be seen from the second floor.

Kingery, R. A., Berg, R. D., & Schillinger, E. H. (1967). Men and Ideas in Engineering. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. (Image of rail p. 59)

Prof. H. F. Moore. (1940s). Alumni and Faculty Biographical (Alumni News Morgue) File, 1882 – 1995. Record Series 26/4/1, Folder: Moore, Herbert Fisher. University of Illinois Archives.