A classroom insight…

During the Fall Semester of 2011, Dr. Kiel Christianson was teaching a version of his Psychology of Reading graduate seminar to a group of Special Education teachers in Iroquois County. One evening, three of the teachers commented that they had several students ranging from 1st through 6th grade who could read fluently, but who were unable to answer even basic comprehension questions about what they had just read. These children were informally termed “word callers,” due to their fluency when reading aloud. Their special education teachers asked for strategies to help these children. Christianson had not heard of students with this description before, but the teachers pointed out that “specific comprehension deficit,” which is what these children were experiencing, was actually in the text book (they were very good teacher-students!).

Dr. Christianson asked how these children did if their teachers read text to them. Could they answer questions then? Their teachers reported that they could, so Christianson suggested that they have the students imagine their parents’ or teachers’ voices saying the words to them as they read silently. In other words, they should simulate hearing a voice speaking the text to them.

The next week, the teachers reported that of the six “word callers,” four of them had tried the voice simulation strategy and, after doing so, had succeeded in answering comprehension questions for the first time. (The two students who didn’t show improvement were 1st graders who didn’t understand the instructions, it seemed.) At the end of that semester, it was reported that all four of these children had been moved out of special education, as their reading had dramatically improved.

A class project…

The next semester, Christianson taught his Psychology of Reading seminar at the University. A psychology graduate student in that class, Mallory Stites, wondered whether text that was described as having been said slowly or quickly would modulate peoples’ reading speeds as they read that text. Stites was inspired by an old paper by Kosslyn & Matt (1977), who found a related effect. Stites wrote up her experiment idea as her final project in the course, and Stites and Christianson ran the experiment in Christianson’s EdPsycho Psycholinguistics Lab (Beckman Institute, 1424) shortly thereafter.

Participants read sentences while their eye movements were recorded with an eye tracker. The results (Stites, Luke, & Christianson, 2013) showed that people do read quotations faster when the quoted speech is described as being said quickly compared to when it is described as being said slowly.

For example, people read the quoted material faster in John walked into the room and said quickly, “I finally found my car keys!” compared to John walked into the room and said slowly, “I finally found my car keys!” (see also Yao & Scheepers, 2011). Stites et al. termed the phenomenon Auditory Perceptual Simulation (APS).

A dissertation…

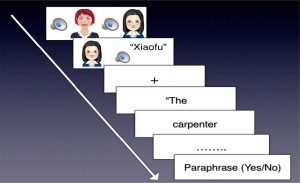

About the time the Stites et al. paper was published, Peiyun Zhou, a doctoral student in Educational Psychology and advisee of Christianson’s, wondered whether APS could be triggered in other ways, such as with cues external to the text that could help struggling readers or second-language learners. Christianson suggested testing whether showing a speaker’s picture might trigger APS during silent reading. This suggestion launched Zhou down a path of over 10 experiments that would eventually comprise her dissertation (Zhou, 2017).

In these experiments, it was discovered that using pictures or voices (or both) to cue readers to simulate faster or slower speakers changed their reading speeds accordingly, as measured again with an eye tracker. Not only that, doing APS while reading resulted in faster reading than when no APS was cued (even when doing APS of slower speakers!). Even more importantly, comprehension accuracy for tricky sentences like The bird that the worm ate was small was significantly better when readers performed APS than when they didn’t (Zhou & Christianson, 2016a, 2016b).

Zhou and Christianson proposed that reading while doing APS is closer to listening to speech, compared to normal silent reading. We listen faster than we read, so this explains some of the increased reading rate. In addition, although we re-read quite often when reading normally, people don’t tend to re-read as much when reading with APS, as we don’t “re-listen,” and APS is more like listening. Further experiments by Zhou using EEG recording of brain waves while reading, performed in Dr. Susan Garnsey’s Beckman Institute lab, confirmed that APS is, even on the neural level, similar in certain ways to listening to speech (Zhou, Garnsey, & Christianson, 2018).

Future applications…

Research continues on APS, including, how and why it works, optimal conditions for its use, its benefits for various populations of readers, and augmenting computer-mediated reading environments with APS. One thing is certain: Developments in APS will grow primarily from ideas and questions generated by University of Illinois students and subsequently fleshed out in the institution’s world-class research facilities.

– Beckman Institute. This is where Stites, Zhou and Christianson conducted their research.

– Education Building. Home of the department of educational psychology.

Kosslyn, S. M. & Matt, M. C. (1977). If you speak slowly, do people read your prose slowly? Person-particular speech recoding during reading. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 9, 250–252.

Stites, M., Luke, S. G., & Christianson, K. (2013) The psychologist said quickly, “Dialogue descriptions modulate reading speed!” Memory and Cognition, 41, 137-151.

Yao, B. & Scheepers, C. (2011). Contextual modulation of reading rate for direct versus indirect speech quotations. Cognition, 121, 447–453.

Zhou, P. (2017). Auditory perceptual simulation during silent reading: effects on language processing and comprehension (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign).

Zhou, P. & Christianson, K. (2016a). I “hear” what you’re “saying”. Auditory perceptual simulation, reading speed, and comprehension. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69, 972-995.

Zhou, P., & Christianson, K. (2016b). Auditory perceptual simulation: Simulating speech rates or accents? Acta Psychologica, 168, 85-90.

Zhou, P., Garnsey, S., & Christianson, K. (in press, 2018). Is imagining a voice like listening to it? Evidence from ERPs. Cognition.